What Is the Advertising Media Selection Problem?

The Advertising Media Selection Problem is a classic combinatorial optimization problem in operations research. A marketing manager has a fixed advertising budget and must decide which combination of media channels — TV, web banners, newspapers, radio, and so on — to invest in, and how many times to run each ad, in order to maximize total audience reach (or expected revenue).

This problem appears simple on the surface, but it involves integer decision variables, budget constraints, frequency caps, and sometimes minimum exposure requirements — making it a natural fit for Integer Linear Programming (ILP).

Problem Formulation

Sets and Indices

Let $i \in {1, 2, \dots, n}$ index the available media channels.

Decision Variables

$$x_i \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0} \quad \text{: number of ad placements in medium } i$$

Parameters

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $r_i$ | Reach (audience size) per single placement in medium $i$ |

| $c_i$ | Cost per placement in medium $i$ |

| $B$ | Total advertising budget |

| $l_i$ | Minimum required placements in medium $i$ (can be 0) |

| $u_i$ | Maximum allowed placements in medium $i$ |

Objective Function

Maximize total weighted reach:

$$\text{maximize} \quad \sum_{i=1}^{n} r_i \cdot x_i$$

Constraints

Budget constraint:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_i \cdot x_i \leq B$$

Lower and upper bounds on placements:

$$l_i \leq x_i \leq u_i \quad \forall i$$

Integrality:

$$x_i \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0} \quad \forall i$$

Concrete Example

A company has a total budget of ¥5,000,000 and is considering the following five media channels:

| Medium | Cost/Placement (¥) | Reach/Placement | Min Placements | Max Placements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV (Prime Time) | 800,000 | 2,000,000 | 0 | 4 |

| TV (Daytime) | 300,000 | 700,000 | 0 | 6 |

| Web Banner | 100,000 | 400,000 | 1 | 10 |

| Newspaper | 250,000 | 500,000 | 0 | 5 |

| Radio | 80,000 | 200,000 | 0 | 8 |

We also add a genre diversity constraint: the number of TV placements (prime + daytime combined) must not exceed 5, to avoid over-concentration in a single medium category.

Additionally, we model a diminishing reach scenario via a multi-segment piecewise approximation — each medium has two cost-reach tiers (first few placements are more efficient).

For clarity, the core model below uses the standard linear formulation; the visualization section extends this with sensitivity analysis.

Python Source Code

1 | # ============================================================ |

Execution Result

======================================================= ADVERTISING MEDIA SELECTION — OPTIMAL SOLUTION ======================================================= Solver status : Optimal ------------------------------------------------------- TV Prime : 4 placements | spend ¥3,200,000 | reach 8,000,000 TV Daytime : 1 placements | spend ¥ 300,000 | reach 700,000 Web Banner : 10 placements | spend ¥1,000,000 | reach 4,000,000 Newspaper : 0 placements | spend ¥ 0 | reach 0 Radio : 6 placements | spend ¥ 480,000 | reach 1,200,000 ------------------------------------------------------- Total spend : ¥ 4,980,000 (budget ¥5,000,000) Total reach : 13,900,000 people =======================================================

Code Walkthrough

Section 1 — Problem Data

All media parameters are stored in plain Python lists: cost_per_placement, reach_per_placement, min_placements, and max_placements. Using list indices keeps the model loop-friendly and easy to extend with more media channels.

Section 2 — ILP Model Construction

1 | model = pulp.LpProblem("Advertising_Media_Selection", pulp.LpMaximize) |

Each decision variable $x_i$ is declared as an Integer with explicit lower and upper bounds — this directly encodes $l_i \leq x_i \leq u_i$. The objective is a simple dot product of reach coefficients and variables. The budget constraint is a single linear inequality. The diversity constraint

$$x_{\text{TV Prime}} + x_{\text{TV Daytime}} \leq 5$$

prevents over-investment in one category.

Section 3 — Solving and Reporting

CBC (the default PuLP solver) handles this small ILP in milliseconds. The result loop computes per-medium spend and reach for a clean tabular summary.

Section 4 — Sensitivity Analysis

A loop over budget values from ¥500K to ¥8.5M re-solves the same ILP at each point. This traces the reach–budget frontier — a staircase function characteristic of integer programs. Each step represents a discrete jump when a new placement unit becomes affordable.

Section 5 — 2D Grid Search

TV Prime placements $\in {0,1,2,3,4}$ and Web Banner placements $\in {0,\dots,10}$ are fixed in turn, and the remaining three variables are re-optimized. The result is a $5 \times 11$ matrix of reachable totals that feeds the 3D surface plot.

Section 6 — Visualization

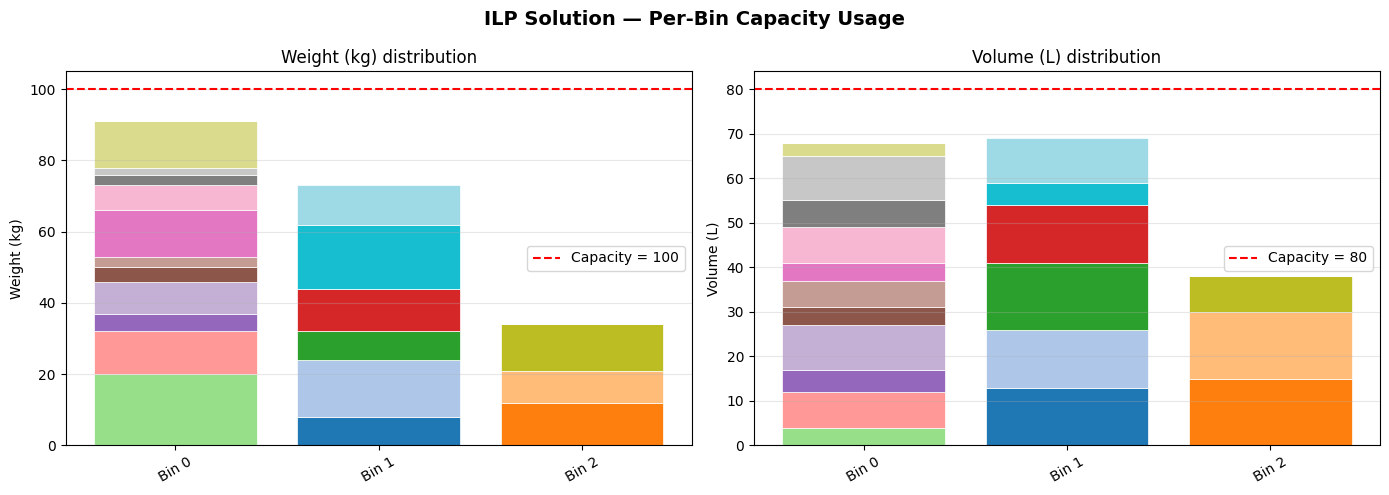

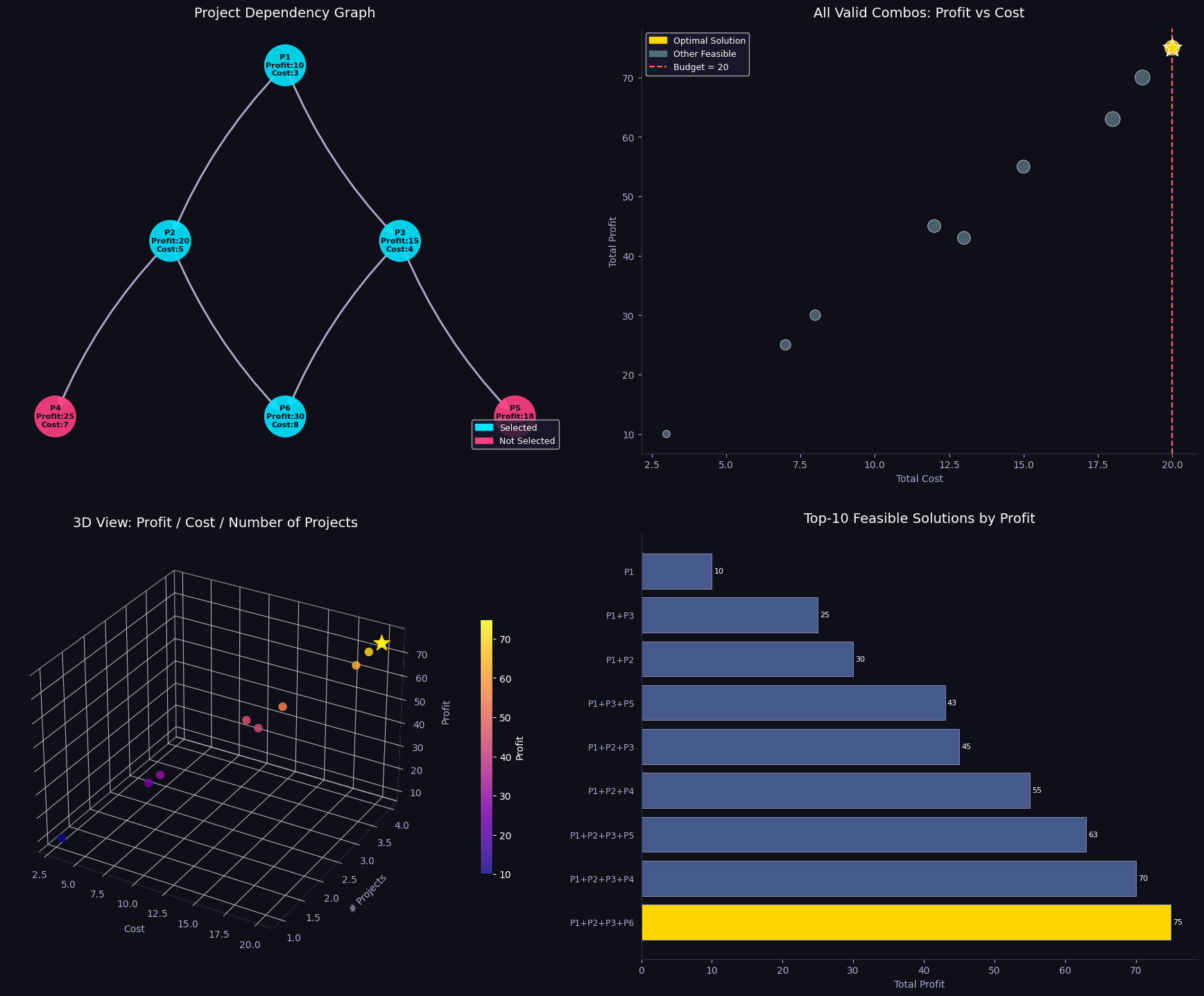

Six panels are arranged in a $2 \times 3$ dark-themed figure:

Panel 1 — Optimal Placements bar chart: shows integer allocation per medium directly from the ILP solution.

Panel 2 — Budget Allocation pie: shows the fraction of the ¥5M budget consumed by each medium.

Panel 3 — Reach Contribution horizontal bar: makes it immediately clear which medium delivers the most total audience.

Panel 4 — Sensitivity curve: the reach–budget staircase. Notice that the curve flattens once all high-efficiency media are saturated — no amount of additional budget helps beyond a certain point in this problem.

Panel 5 — Cost vs Reach scatter (bubble): each bubble represents one medium. Bubble size is proportional to reach efficiency $r_i / c_i$. Media in the upper-left quadrant (high reach, low cost) are the most attractive single-unit investments.

Panel 6 — 3D surface: the $z$-axis shows maximum achievable total reach (in millions) as a function of TV Prime placements (x-axis) and Web Banner placements (y-axis), with all other variables re-optimized. The surface is computed by the grid search in Section 5.

Key Insights

The ILP formulation captures the discrete, integer nature of ad placements exactly — you cannot buy 2.7 TV spots. The staircase shape of the sensitivity curve (Panel 4) is a hallmark of integer programs: the feasible set is a lattice, not a convex polyhedron, so the objective improves in discrete jumps rather than continuously.

The 3D surface (Panel 6) reveals the interaction structure: for low web banner counts, adding a TV Prime placement gives a large reach boost, but as the budget fills up, the marginal gain of extra TV prime slots shrinks because the diversity constraint kicks in and forces the optimizer to substitute cheaper media.

The efficiency scatter (Panel 5) shows that Web Banners offer the best reach-per-yen ratio among the five channels — yet the ILP still allocates budget to TV Prime because its absolute reach per placement is so large that even at high cost it clears the budget-adjusted hurdle in the optimal mix.